Where can the purest principles of morality be learned so clearly or so perfectly as from the New Testament? Where are benevolence, the love of truth, sobriety, and industry, so powerfully and irresistibly inculcated as in the sacred volume? — The U.s. Supreme Court, 1844

We’ve all heard the phrase “separation of church and state,” but most of us are unfamiliar with its American origin. Most of United States citizens take it to mean that everything in the public square must be secular and no government employee, entity, or property is allowed to express anything religious in nature or display any religious symbol. But is this what our founding fathers intended when they added the phrase “separation of church and state” to The Constitution?

Oh, my bad. The phrase “separation of church and state” appears nowhere in ANY founding document, not even in The Constitution. But still, the founders surely intended there to be a wall of separation to prevent any religious expression in the public square, right?

No, not so much.

Let’s start out with what The Constitution actually says about religion and religious freedom. The relevant part of the 1st Amendment says:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…

The establishment clause merely means that congress shall not form, or establish, a national denomination. That’s all there is to it. The free exercise clause means that each individual has the freedom to exercise their religious conscience and no law can ever prohibit it. It’s that simple.

So why do so many of us believe “separation of church and state” is a founding principle? Because the courts have twisted and warped the meaning of the First Amendment to fit their own dogma, and history is no longer taught as it once was.

History of “Separation of Church and State”

On October 7, 1801, baptists of Danbury, Connecticut, wrote a letter to the recently elected President Thomas Jefferson. In it, they praised him for his character and for his election to the presidency. Then, they addressed a deep concern:

Our sentiments are uniformly on the side of religious liberty: that Religion is at all times and places a matter between God and individuals, that no man ought to suffer in name, person, or effects on account of his religious opinions, [and] that the legitimate power of civil government extends no further than to punish the man who works ill to his neighbor. But sir, our constitution of government is not specific…

Therefore what religious privileges we enjoy (as a minor part of the State) we enjoy as favors granted, and not as inalienable rights.

The Danburys were concerned that since a government document (The Constitution) mentioned the right of the free exercise of religion, this meant that the right was granted by the government, and therefore alienable. They felt that the right to religious expression and religious conscience was granted by God and therefor inalienable. The Danburys’ concern was if the government thought the government granted the right, then the government may someday regulate it, limit it, or interfere with it.

Jefferson replied on January 1, 1802:

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God; that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship; that the legislative powers of government reach actions only and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between Church and State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties.

The “natural rights” that Jefferson alluded to are the rights granted by nature and nature’s God, those same rights founded in scripture. Jefferson was emphatically stating that the free exercise of religion and religious conscience was indeed inalienable and not under the jurisdiction of the federal government. It could not be regulated, limited, or interfered with.

Since it was a private and personal letter between one man and one obscure organization, Jefferson’s letter to the Danbury Baptist fell into obscurity. Well, for 76 years anyway. It was invoked in 1878 in the case of Reynolds v. United States. The court of the time cited a large portion of the letter, reaffirming Jefferson’s point that individuals have the freedom to exercise their religion, even in public, and that religious exercise can only be interfered by the government if the religious exercise breaks out “into overt acts against peace and good order.” The court would define these “overt acts” as human sacrifice, bigamy, polygamy, advocating licentious behavior, etc.

Jefferson’s letter again fell into obscurity until 1947, in the case of Everson v. Board of Education. Instead of quoting Jefferson’s entire letter in context, the court cited only the 8-word phrase: “a wall of separation between Church and State.” And boom! The remolding of the 1st Amendment began and a new wall began being built. The court stated:

The First Amendment has erected a wall between church and state. That wall must be kept high and impregnable. We could not approve the slightest breach.

Hmmm.

A few things here are noteworthy. The need for religion was mentioned in the Northwest Ordinance, an ordinance enacted in 1787 by the United States government to help aid in populating and governing new territory of the country. Article 3 of the ordinance reads:

Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.

Not only is religion listed with other necessities, it is at the top of the list. If our founding fathers wanted religion out of the public square, they would not have mentioned religion among the other necessities.

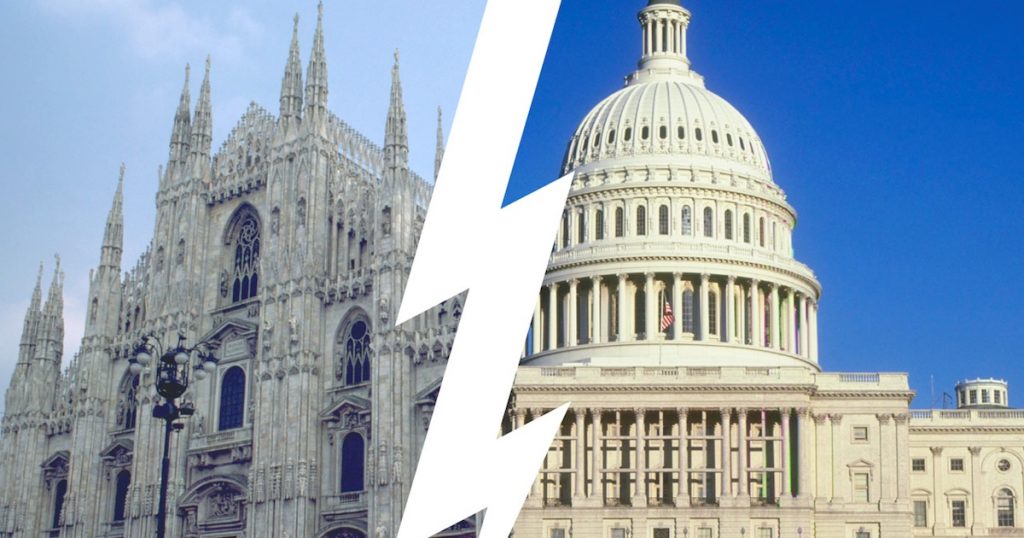

Another thing to note: Jefferson attended church the weekend after he wrote his reply to the Danburys. “So what?” you say? “Lots of public officials enter church buildings on Sunday.” Wait, wait. I’m not done. Where did Jefferson attend church the very Sunday after he wrote the now famous Danbury letter? The letter that modern-day courts use to prove that Jefferson opposed everything religious in the public square or on government property? Jefferson attended church in the United States Capitol Building – one of the most famous government buildings.

Congress, in late 1800, had approved the use of the building as a place of worship on Sundays. Oh, and Thomas Jefferson was president of The Senate at the time. If the founders, including Jefferson, opposed all forms and expressions of religion in public, surely they would have raised a fuss about this congressional approval of the Capitol Building being used as a church. Even then, as principled as Jefferson was, if he opposed religious expression in public, he would not have attended church in the Capitol Building. Jefferson attended church services there his entire presidency, riding there on horseback, including Sundays which had poor weather. He was quite obviously fine with religion in the public square. But modern-day courts have used Jefferson’s own words, divorced from context, to contradict Jefferson’s other words and actions.

Courts in the past disagree with the court of 1947 and other modern-day courts. In Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, 143 U.S. 457 (1892) the Supreme Court stated:

Among other matters, note the following: the form of oath universally prevailing, concluding with an appeal to the Almighty; the custom of opening sessions of all deliberative bodies and most conventions with prayer; the prefatory words of all wills, “In the name of God, amen”; the laws respecting the observance of the Sabbath, with the general cessation of all secular business, and the closing of courts, legislatures, and other similar public assemblies on that day; the churches and church organizations which abound in every city, town, and hamlet; the multitude of charitable organizations existing everywhere under Christian auspices; the gigantic missionary associations, with general support, and aiming to establish Christian missions in every quarter of the globe. These, and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic utterances that this is a Christian nation.

In this case, the Supreme Court cited dozens upon dozens of precedents. These precedents, over 80, included quotes from founding fathers, other laws, and other government documents, that point to our country being an openly religious nation. They even cited Article I, Section VII of The Constitution to point out Sabbath Day observance.

In Vidal v. Girard (1844), the Supreme Court pointed out the value of The Bible, especially The New Testament, being studied in public schools:

Where can the purest principles of morality be learned so clearly or so perfectly as from the New Testament? Where are benevolence, the love of truth, sobriety, and industry, so powerfully and irresistibly inculcated as in the sacred volume?

Believe it or not, in the early decades of our country, most school houses only used one text book: The Bible (gasp!). Founding father Benjamin Rush, a man of science and a man of faith, promoted this doctrine in a letter he wrote in 1830.

For over 150 years, the court and other government officials continually reaffirmed that the 1st Amendment’s establishment clause referred to congress not being allowed to establish a single national denomination. This is also backed up in the notes from the debates which resulted in the wording of the 1st Amendment. The founders’ intent was made abundently clear: they simply didn’t want what they had had in England, a single denomination over the country. That’s all. They were fine with religious activity and religious talk in public. This was national policy, backed up by original sources and precedents, for over a century and a half.

Then, in 1947, in the case of Everson v. Board of Education, Justice Hugo Black, an FDR appointee, a defender of pornography, and a KKK member, misinterpreted and remolded a small phrase of Jefferson’s letter, “a wall of separation between Church and State.” Black divorced Jefferson’s letter from context and from previous court decisions. Jefferson’s private letter, which reaffirmed a church’s protection from the state, began to be used by the state as a weapon against religion.

After 1947, the phrase “separation of church and state”began to be used more and more in court, with the judiciary explaining that this is what the founding fathers wanted, without ever quoting the founders, and while ignoring past court decisions protecting religious activity in public. This prompted a fed-up Judge Gallagher, of the New York Supreme Court, in Baer v. Kolmorgen (1958) to dissent:

Much has been written in recent years… to “a wall of separation between church and State.” It has received so much attention that one would almost think at times that it is to be found somewhere in our Constitution.

It, of course, is not found in any founding document, let alone our constitution. But Hugo Black of the supreme court used the phrase to facilitate his open hostility towards religion.

15 years after his 1947 opinion of Everson v. Board of Education which turned the religious clauses of the 1st Amendment upside down, Hugo Black and his cohorts banned school prayer in Engel V. Vitale (1962). Prior to this anti-liberty judicial opinion, the word “church” in the “separation of church and state” phrase was defined as a federally established denomination. But Hugo Black redefined “church” to mean a religious activity in public. With prayer definitely being a religious activity, it fit Black’s redefinition.

Remember the numerous precedents I previously mentioned in Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States (1892), which abundantly illustrated our country’s religiosity from the founding up to that point, and supported religious expression and activity in public. There were over 80 precedents in that case. So, how many precedents did Hugo Black cite in Engle v. Vitale (1962)? Just one. And he cited his own opinion from the 1947 case Everson v. Board of Education. Rather incestuous, eh? However, his citation to his own opinion was only to reference an obscure historical reference. This citation was not intended to support his new 1962 decision however, it was merely citation for citation’s sake. So, in reality, Engel v. Vitale, the landmark judicial opinion, cited ZERO precedents to back-up Black’s tyrannical ban of public prayer. Zero. He simply said that they were banning prayer.

New law. New precedent. Damn the majority of the public that want school prayer. Damn the legislative branch. We are going to create the law that we want. We are going to feed the canard that this is what our founders wanted all along. We are going to inaccurately cite a private letter from Jefferson, one founding father, to support this canard. We don’t need to cite any actual founding document, or any other quote from Jefferson, or any quote from any other of the many many founding fathers. We don’t need to cite original intent. We don’t need to cite The Constitution, the very document we swore to uphold. Even though The Constitution does NOT give us authority to do so, we are going to declare all sorts of stuff as unconstitutional. After all, we are the high-priests of the law and we know better.

Shortly after this anti-constitutional act of Black’s court, he and his cohorts banned Bible discussion in schools, religious discussion in schools, and banned religious symbols, including The Ten Commandments.

As a side note, even though Jefferson is often cited as the father of the 1st Amendment, he did not write the 1st Amendment. He wasn’t even involved during the debates. In fact, he wasn’t even in the country at the time. But by all means, lets let an out-of-context 8 word phrase from a private letter he wrote determine 1st Amendment national policy. After all, that is what the founders wanted all along.

Separation of church and state is a canard spawned by the activist, tyrannical, anti-constitutional, anti-religious supreme court justice Hugo Black.

And Jeffrey Epstein didn’t kill himself.

I nearly split open my new appendix scar when I read the last sentence. So out of the blue, but still true.

That totally blew me away about President Jefferson attending church in the capital building. I had no idea it doubled as a church. That is good enough evidence for me. The way historians today depict Jefferson, he hated all forms of religion and would practically use The Bible as toilet paper. I really think that Jefferson is one of the most complex and most misunderstood figure in american history.

😀 Glad I nearly gave you a burst surgical scar.

And I agree, Jefferson is very misunderstood. Several founding fathers’ quotes are continually cited out of context in several history books and websites, but I think that Jefferson may be the most misquoted. And you are right, he is very complex. I’ve read several dozen books about him, and they all contradict each other. Original sources are key. This is why I only read Jefferson’s actual words, in full. He is not understandable otherwise.

An for those who don’t know, there is NO evidence (DNA or original sources) that Thomas Jefferson fathered any the offspring of Sally Hemings.

What bull****!

This is the problem with all you trump ***holes, you cherry pick just a few things out of history and ignore the rest that disproves your argument. The founding fathers were deists and wanted to escape religion. John Adams one of the founding fathers said that this would be the best of all worlds, if there were no religion in it. He also said that this is not a christian nation.

Read The Godless Constitution. You know, never mind, reading comprehension obviously isn’t a strong gift for you.

Get your head out of Trumps ***.

Hi Rick,

Thanks for reading my post. Would you please be kind enough to point out where I have erred? I would be willing to correct any mistakes.

Yes, I am quite familiar with the quote you mentioned from President Adams, although it is completely divorced from context. Here is the quote in full:

“Twenty times in the course of my late reading have I been on the point of breaking out, ‘This would be the best of all possible worlds, if there were no religion at all!!!’ But in this exclamation I would have been as fanatical as Bryant or Cleverly. Without religion, this world would be something not fit to be mentioned in polite company, I mean hell.”

John Adams meant the exact opposite of what you quoted. Religion is necessary.

In all my study and research, I have yet to find a valid citation that quotes Adams as saying this is not a christian nation. I think the quote you are referring to actually comes from the 1797 Treaty of Tripoli in Article IX (John Adams was president at the time):

“The government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion.”

This quote is one of the most used quotes from those who decide to ignore all the original sources from founders declaring this nation to be a religious or a Christian nation. Problem is, the sentence does not end where that quote ends. Here it is in full:

“As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen [Muslims] and as the said States [America] have never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.”

I don’t have time to go into a history of what led up to the Treaty of Tripoli. Summarized, the Barbary Powers War was the United States’ first war on Muslim terrorists. What the quote means, in context, is that the U.S. should not be counted among the other christian nations which had already declared open hostility towards Muslims, so there was no reason to war with the U.S., that we didn’t have a “jihad” against them. In other words “We have no quarrel with you. Let’s not fight.”

The war, however went on, costing money and lives, despite the treaty. In order to keep the Muslim pirates from warring with us, we paid them off. But they still plundered and killed. So we payed them more. They still plundered and killed. The payments, by the time Jefferson became president, accounted for nearly 20% of the federal budget. Jefferson was fed up. This is why Thomas Jefferson owned a copy of the Quran, so as president, he would study the Quran and learn about the enemies of the United States. It was because of his studies, that he correctly concluded that the Muslim pirates wanted to fight, because killing Christians would satisfy their jihad needs and in their eyes gain them salvation. Jefferson stopped the payments and began military action.

And as for The Godless Constitution, I have read it. I found it lacking any evidence. In the copy I read, there was no bibliography, so no citations. I don’t know if subsequent editions included a bibliography or not. They failed to cite original sources and ignored actual evidence that proves their main point wrong.

Again, I ask you where I have erred?

I’ll show you were you errored. The framers of the constitution hated religion.

Article 6, no religious test for federal office.

Godless Constitution.

No religion.

Hi Rick,

Thanks for responding.

The “no religious test” clause of Article VI does not mean the framers wanted a secular nation or that the framers were hostile to religion. They merely didn’t want a test at the federal level, since they felt religion wasn’t under federal jurisdiction. They also feared that having a religious test at the federal level would supersede already existing religious tests in state constitutions. This is made evident by reading the notes taken at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Many of these individuals who supported the Article VI religious test ban were responsible for pro-religious test wording in state constitutions.

Here is a religious test of the Pennsylvania Constitution:

“And each member, before he takes his seat, shall make and subscribe the following declaration, viz:

I do believe in one God, the creator and governor of the universe, the rewarder of the good and the punisher of the wicked. And I do acknowledge the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by Divine inspiration.”

Another state constitution required state officials to be Protestant.

And, although this doesn’t have to do with religious tests, I want to quote the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which were used to form The Declaration of Independence and later The Bill of Rights:

“That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it, can be directed by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore, all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practice Christian forbearance, love, and charity towards each other.”

Holy crap! That state religious test is incredible. I had no idea. And the Virginia thing is shows that they were Christian.

Incredible. To see it all laid out like this is eye opening. It really does seem like there is evil actively going after religion and liberty.

You will be happy to know that the information in this article got my anti-religious pro-separation Aunt to rethink her defense of church and state. She literally had thought “separation of church and state” was in The Constitution. When she read in your article, that it was not in The Constitution, she called you a liar. I challenged her and she looked up The Constitution and actually read it. She had nowhere to go from there. Her wall cracked, and crumbled.